One gusty day in May of 1997, a mailman trudged down the streets of Fort Greene in Brooklyn and plucked a letter from his bag. It almost flew from his hands, but it didn’t, and he dropped it through the stiff brass mail slot of a sober, liver-colored brownstone, where it lay on the dulled parquet until Lou Orsini, who’d lived forever on the second floor, scooped it up, almost tossed it out with the Panda Garden delivery menus, but didn’t. He saw it in time and propped it on the stairs. When Ulla and Sunny returned from the Korean deli with toilet paper, tofu, sprouts, and six assorted artisan ales, Ulla almost trod on it but didn’t. She made pincers of her fingers and picked it up despite her hands being full. Ulla was the girlfriend Sunny had never happened to mention to his family, although for more than a year now they had shared a lease, a bed, a Con Ed utility bill, a laundry basket, and, on some absent-minded occasions, a toothbrush.

“What does your mother say?” Ulla asked, unlacing her sneakers.

Sunny would come to regret not bundling the letter away, but in this moment it was so astonishing that he exclaimed, “Look! I have a marriage proposal!”

Oh, how could he have forgotten that love, when it arrives, arrives always twinned to its destructive force, as inevitably as God and Devil, life and death, home and the leaving of it; that information collected during sweeter moments will be turned to ammunition and discharged during war; that what is innocent in the morning will not remain so at nightfall.

Ulla took the letter from Sunny.

“My dear boy,” Babita Bhatia had penned in her customary envy-green ink.

As a boy, Sunny used to put his fingers in his ears and shout, “Mummy, please stop this gossip!” But her letters held a grotesque fascination for Ulla, who found them as riveting as “Masterpiece Theatre.”

Sunny had explained to Ulla that Vinita and Punita were his mother’s servant girls, daughters of his mother’s cleaning maid, Gunja, who had eight living children—three had died in infancy (Babita used the phrase “popped off”)—and Gunja’s husband was a drunk who sold chicken and mutton bones for a living, collecting them from dhaba eating places, then transporting them to a bone-meal-fertilizer factory. Gunja could not afford to have six daughters at home; she’d have to marry off the two oldest girls. To give Vinita and Punita a little more time, she begged Babita to keep the children in exchange for housework. Vinita, the elder of the pair, had already been taught how to make pigs in blankets and a chicken-liver pâté with brandy; the younger one, Punita, was enrolled in a neighborhood charity school but helped her sister in the evenings. Even though she had two servant girls for free, Babita was to her mind involved in a social experiment to uplift society.

The gray modernist house in which the Bhatia family lived had been designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier’s and built by Sunny’s paternal grandfather, a former finance minister who had swiftly acquired several palatial properties in a manner that could be explained only by corruption, although by the time Sunny was born the properties had been lost to further corruption, save the Panchsheel Park house, which had been sectioned into three, one-third for each of the minister’s sons, Ravi, Ratan, and Rana. When Sunny was eight, his father, Ratan, died of a heart attack, and nobody in his father’s family had spoken to Babita since—they accused her of driving Ratan to despair with her harangue. Sunny’s widowed grandmother had composed a will leaving the property, which was in her name, to Ravi and Rana, compensating Babita with a slim portfolio of investments and a set of Spode eggcups in a woodland-rabbit design, which she had always coveted.

The value of the investments had fallen, and Babita contested the will in court, but, because the courts were so overwhelmed that they usually resolved such cases well after everyone involved was dead, she expected to stay on in Panchsheel Park until her own demise.

When Babita exited her front door, she turned her nose up and to the right if she saw elder brother-in-law Ravi to her left, and she turned her nose up and to the left if she saw younger brother-in-law Rana to her right. The eggcups, held ransom, resided in brother-in-law Ravi’s glass display cabinet, and once in a while, to annoy his sister-in-law, he lingered over breakfast in his garden, where she might espy him gloating in his paisley dressing gown: “My, oh, my, what a cunning eggcup, and is this little Peter Rabbit under the blackberry bush?”

When Ulla laughed, exclaiming, “Crazy!,” Sunny saw an ageless Ulla, all the way from what she must have been as a pixie baby to what she would be when she was a pixie ancient.

Ulla opened the second letter enclosed with Sunny’s mother’s letter, and she pounced. “What’s this?” And there was Sonia. Tall, slender, a braid down to her waist, standing against snow-laden Vermont firs, in a disconcerting, mustard-colored coat.

“It’s the custom to send photographs, of course,” Sunny yelped, but he dared not peek. The shift in Ulla’s voice made him adopt an impenetrable expression as he put his laptop, which resembled a tubby flying saucer, into his satchel. Just another half hour and he could exit with the righteous haste of someone on his way to work. Sunny worked the night shift at the Associated Press, where he had been employed straight out of his graduate program at Columbia University, in an entry-level position, learning the rules of the A.P. Stylebook, editing and sending out on the wire the news that came winging in at all hours. His part in the enterprise was small, but it felt crucial because the stories were urgent: thirty Black churches in the South burned to the ground in eighteen months; there was violence between Israel and Hezbollah; an earthquake hit China; Osama bin Laden declared war on the United States; and Charles and Diana divorced. Sunny longed for the day he might see his byline in a print newspaper and considered pitching a story to the news desk; it was permissible to do so.

Ulla, annoyed by his vague expression and his desire to flee from his mother’s missive, said, “Are you sure this letter is innocent?” If he weren’t behaving guiltily, Ulla wouldn’t have been suspicious. If she weren’t suspicious, he wouldn’t be behaving guiltily. To have kept Ulla hidden from his mother, as he had, or to remember his Indian life made Sunny turn from Ulla sometimes. It was his remoteness in these moments that made Ulla long for him even when he was in the room, which made her love him more despite their arguments, and be provoked by him more, which increased their arguments.

“There’s nothing sinister about the letter,” he said. “Everyone gets these at my age, forwarded by relatives, friends, people who’ve never set eyes on you—a great pile arrive when you finish college, and the flood continues until everyone is settled. Then there is a lull before they begin marrying off the progeny of these mishaps, each generation lesser than what came before, because what hope can you have from such a process?”

At this moment, Sunny’s phone rang. Sunny and Ulla maintained two phone lines so that Sunny could give his mother his private number and tell her that he lived with a housemate. Both Sunny and Ulla knew the caller would be either his mother or Satya, his closest friend, who telephoned him daily.

Sunny didn’t answer the phone. “I am an ineligible, poor journalist, so only one such letter has arrived,” he said, placating Ulla a little more. “Satya, who is going to be a doctor, must have a hundred. Whenever he gets depressed, he orders takeout from Punjab Hut, locks himself in, listens to old film songs while rereading his marriage proposals, and he cheers up.”

This didn’t cheer Ulla, however. She had first thought Sunny was shy, if a bit childish in his inability to admit openly to a relationship. But now she understood the consequences and perhaps the true purpose of this secrecy: Sunny was keeping his options open. “Surely,” she said, “surely your family in India realizes that it is disrespectful to me?”

Silence.

Ulla yelled, “They don’t realize it is disrespectful to me, because they don’t know I exist!”

Sunny kept his gaze averted. “Look, however progressive my mother is, she is an Indian woman from another generation. Do you really think I can tell her that we sleep in the same bed? If I was taking this proposal seriously, wouldn’t I have hidden the letter instead of saying, ‘Look, Ulla’?”

Ulla sighed. “I should be feeling angry, and I am so angry, yet I also feel bad for this poor girl who is being marketed. It’s a scandal that they treat women like this.”

“Well, they treat men the same way and you’re not showing me sympathy.”

At 9 P.M., Sunny fled for the subway, wishing he were as uncoupled as the purple wind that blew through the city. Even in this country, where he’d assumed love was different from the Indian version, it was not a private endeavor, but a public event. If you didn’t stamp and stamp love with legitimacy and acknowledgment, and stamp it some more, silver and gold, with further legalities and recognitions, the ghost of future lost love infiltrated, and your love became irrevocably unformed, the lack folded into its substance.

In the elevator of the Associated Press Building at Rockefeller Plaza, Sunny’s brows trembled. He observed his clay-colored shoes, the geometric print of his navy shirt. He remembered the story about a Chinese philosopher who had dreamt he was a butterfly. The dream had inspired the question: Was he a man dreaming he was a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he was a man?

He couldn’t articulate to Ulla, lest she claim to be the victim of his ambivalence, that his life now seemed at a remove, that it was sometimes unrecognizable even to him. Whenever he walked up the creaking mast of stairs to their seagull’s-nest apartment, he was surprised anew by Ulla’s elfin beauty, by the pine floors, by the white Ikea couch, by the Western lightness and comfort that were, apparently, his. He often couldn’t determine exactly how he felt about his new life, and it was how he happened to behave at such times that elucidated his emotions. But he was also unsure whether he was behaving from honest impulse or merely playing a part, taking his cues from the people, the weather, the food, even the objects around him: the bowl from a North Carolina potter filled with farmers’-market heirloom tomatoes; the deceptively simple cut and calm gray of his first coat that was not a parka; snow and darkness in the afternoon; an omelette filled with smoked salmon and dill cream cheese.

One thing seemed certain: if India existed, then America could not, for they were too drastically different not to cancel each other out. Yet, despite this fact, they refused to remain apart. India invaded his life all the way from the other side of the world, and then life here became instantly artificial. He became an impostor, a spy, a liar, and a ghost.

By 10 P.M., Sunny had settled into his cubicle in the deserted newsroom. He was editing a story on Dolly the cloned sheep when his phone rang. He knew it would be his mother. He had thought he would be able to love her better from New York.

Sunny and Ulla had first met by Riverside Park, in the cafeteria line of a hostel for international students and American students interested in an international experience. This hostel may have had an academic purpose, and it may have looked staid from the outside, but in actuality it was a hysterical airport of love affairs as students from around the world—menaced by perpetually expiring visas and the panic of limited time—romanced one another in fast-forward, having but two or four years to trick their native fate, leapfrog into another nation, another class, another skin, and to sample all the world offered. It was a wonder anyone managed to achieve a degree.

A Danish dancer chased a Senegalese student of engineering; a Hungarian Communist teacher’s son stalked an American soy-sauce baron’s granddaughter; a girl from the Midwest tracked the lone Scotsman. There was a slapstick randomness to these loves conducted in dozens of languages during movie nights or dance lessons, or in the cafeteria, where everyone went despite the dullest food in the city in case a potential romance awaited by the steamed-vegetable medley.

For Sunny and Ulla, these were their most joyful days: when he had first found himself vulnerable to her hedgehog hair style and the way she swayed so freely at ballroom dancing; when she had first been stirred by the old-fashioned grandeur of his hawk nose and his hawk eyes, his formal bearing and correct manner as he waited with his food tray and his folded New York Times, reminding her a little of her Kansas grandfather who had emigrated from Sweden.

Ulla lived in a part of the hostel that was divided into mini apartments—three students sharing a kitchenette and a bathroom—and one of the young women in Ulla’s apartment, Mala, came from Delhi, just like Sunny. He’d been considering asking Mala to broker a formal introduction to Ulla, when one night in the cafeteria, as if Mala had divined his interest, Sunny overheard her begin to denounce the disheartening and repetitive occurrence of Indian boys running after white American women, always picking the most pallid, androgynous ones, the kind who withdrew to spend moody hours scribbling in diaries. This was what attracted them, Mala said, because no Indian woman was allowed enough privacy to thus indulge in a solipsistic obsession with her own psychology—encouraged to chart the fluctuations of her temperament in response to deep crises that were inevitably banal. These women, meanwhile, realized they could snag a Third World man far higher up the ladder of class and money than any fellow-American, with whom their prospects were dim, simply by using the bargaining power of their citizenship and their pale complexion.

“You’re Mala’s friend,” Sunny said, when he realized he’d have to address Ulla directly.

“I wouldn’t put it quite like that,” Ulla responded.

“Why not?”

They built their first bond, Sunny and Ulla, on their mutual resentment of Indian women in general and Mala in particular, tumbling into this conversation because they had no other. No matter what Ulla was doing, Mala had to be doing that and something better, Ulla complained. “If I say I’m working at a summer camp in Maine, she says she’ll be working at an orphanage associated with the Dalai Lama. And she is applying for a Fulbright. If there are two peaches, Mala has to eat the best peach, or both peaches. She would never in a million years eat only the lesser peach.”

Sunny gave a little bow of acknowledgment both externally to Ulla and, secretly, internally, for he had identified similar embarrassing hungers in himself but was determined to suppress them and loathed them in others. Something about arriving in America, he’d observed, made one want to grab enough for past, present, and future all at once. He wanted to protect America from those like him, but then, if others were gobbling and grabbing, he should, too, or he’d be left behind. The next instant he felt sickened by self-disgust. That was why he ran from Indian women, he told himself.

“Why do they do it?” Ulla asked.

“Well,” Sunny said, “in India there are too many people and men control everything, so they have to get what they want in primitive ways, with fake friendliness. Here there is much less opposition and much more to gain—so here, my God, these women become monsters.”

Thus Sunny adopted an expert’s role on the unfortunate qualities of Indian women, oblivious of the fact that, before Mala and Ulla’s friendship had been tattered over peaches, Mala had educated Ulla on the miserable personalities of Indian men: Indian men and their controlling attitudes, Indian men and their mummies, their jealousies, their pride, their rages and entitlements—the way they became lecturing gurus telling everyone everything about everything before the first gray hairs fringed their ears, the way a disproportionate number were driven by the ambition of finding a white woman—all the better to escape India.

“Why?” Ulla had asked.

Well, Mala had said, they might then reclaim India with dignity once they had a safety raft and finally manage to be nice to fellow-Indians so they could make use of India in earnest now that they had lost the fear of being swallowed back. Or they might go in quite the other direction and pretend they were not Indian at all. Say all the bad things about the country so white people didn’t have to.

Either way, they no longer lived an honest life, Mala said.

Sunny was touched by how Ulla’s dislike for Mala hadn’t translated to dislike for all Indians. Or perhaps he was flattering himself into thinking he was therefore utterly unlike other Indians.

And Mala had made one severe misjudgment: Ulla wasn’t outraged by Indian men chasing American women. She loved to be desired, and if being American or freckle-skinned or a pixie blonde delivered her to the top of the heap, well, would any woman turn away from her natural advantage?

Only later did Sunny wonder if Mala had both made their relationship possible (Indians were no longer foreign or unknowable to Ulla) and also impossible (she had provided Ulla with all the avenues of complaint). Certainly, together Sunny and Mala had granted Ulla a complete lexicon of arguments against Indians, male and female. As if each gender of a certain class, the Westernized class, hoped to make it in the United States by waging mutual war. It was because of Indian men that Indian women were forced to run. It was because of Indian women that Indian men would do anything to get away.

For the first days of living with a girlfriend, everything had been surprising—the fact, for example, that Ulla and Sunny had different ideas of privacy. Astonished to find no lock on the bathroom door of their new home, Sunny rushed, expecting Ulla to come in at any moment, and she often did, wandering in to chat about trivial matters while Sunny was in the shower, or even to nonchalantly pee. When he went to the hardware store to buy a latch, she collapsed into giggles: “How can you be so shy!”

She would throw off all her clothes and wander about the apartment, delighting in the Brooklyn sunshine spangling through the leaves of a maple.

“It’s far easier,” Ulla, however, said, “for you to say you’re from Delhi than for me to say I’m from Prairie Hill, Kansas. New York favors foreigners.”

Sunny had been startled to discover that Ulla’s real name was Mary but that she had decided in high school to go by Ulla. Frequently, when asked where she was from, she said New York City, not Prairie Hill, betraying the place she loved and which she could enchant Sunny with by recalling a land so flat and empty you could see your friends arrive from miles away, where stars blossomed at your feet at nightfall, where the wind never stopped tussling.

Ulla showed Sunny how to snip open cartons, buy fabric softeners and dryer sheets, telephone for a gas connection, order a hamburger. (How lucky she was to be with a Hindu who ate beef she had no idea.) She gave him all the information on American life that you couldn’t get from having read “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” or “Slaughterhouse-Five” or “Two Serious Ladies.” These stories had not been practically useful, but it was the eccentricity of America and Americans as conveyed by them which had first powerfully drawn Sunny to this country.

If Ulla enjoyed her role too much to be discreet about it, she was nevertheless kind and painstaking. “Say ‘A,’ ” she said. “Say ‘P.’ ” She tutored Sunny to pronounce words so he would be understood: “parrot” not “barrot,” “vegetable” not “wedgetable.” She taught him to say “Good!” when asked how he was instead of “Terrible,” because nobody likes a cynic.

By then, Ulla was collecting proof that he avoided words like “bra” or “panty hose.”

“Say it!” she would insist. It was presented as a game, but he experienced it as a taunt, and, as he more intractably refused and nurtured the beginnings of resentment, Ulla began to feel oppressed in turn.

“If you tried to dance,” she said with some bitterness, “you might like to dance.”

“Why don’t you eat fish?” Sunny responded.

“She eats only salad for lunch, and when she orders pizza it’s always a plain cheese pizza,” Sunny reported to Satya.

Not only did Ulla prefer a pizza pie without anything but a tomato base and mozzarella, Sunny had discovered she considered a simmering complexity of sauces or a mix of spices a barbarous invention. Should a puddle of yellow begin to race across the plate to join with a puddle of brown, she felt fear. When they went out to eat, she prayed with all her concentrated might the restaurant would be Italian.

They began to notice that although they could each be stung at various times by their own inadequate cosmopolitan flair, they rested their pride on their vulnerabilities—on refusing to give up what, perhaps, they most hoped to lose. And what they most hoped to lose, then, was what they fought for most and what most defined them. At a certain point, it became a tragedy. A tragedy when you took the wider perspective and considered the fact that Sunny belonged to the first generation of men of his class in India who actually cooked and didn’t direct women and servants while claiming the praise.

“Whatever I eat, I find he’s slipped curry in there,” Ulla announced in the indulgent tones of the owner of a weird foreigner to a group gathered at a tapas restaurant to celebrate the birthday of Ulla’s friend Natalina, who used the occasion of having an Indian at the table to recount a recent trip to teach the women of Rajasthan how to use solar ovens: “My God, being a blond woman travelling alone in India, they just go mad—they cannot conceive of you as a person. A man on the platform reached through the train window and grabbed my breasts, and as the train began to leave the station he ran along with the train, still holding on.”

Sunny steadied a slight tremble in his hands by very precisely slicing a bacalao croquette using a knife and fork. Wasn’t there a suggestion that he was in some way responsible, in a long series of associations? He felt insulted and guilty, then annoyed at having to feel guilty or insulted, especially while eating at a restaurant in the West Village that would gouge his bank account. He delivered a triangle of tortilla española neatly to his mouth and chewed with his lips firmly closed, to place himself at a level of civility far removed from his nation, to prove with his table manners, familiarity with the foods of Spain, and sympathy for female travellers that he was not like those men to be found on every street corner in India, staring lustfully, bestially, as if they were no longer human, at women they didn’t consider to be human.

“Did you get sick?” someone asked. “I hear everyone gets sick in India.”

Sunny sipped his Basque wine. Secretly he was thinking that this woman had some nerve to fly across the world from her New York City apartment—no doubt equipped with a stove, microwave, toaster, fridge, blender, coffeemaker, hair dryer, vacuum cleaner, television, computer, music system, heater, fan, and air-conditioner, if not also a bicycle or car—to tell women in India to cook their rice in a cardboard box covered with silver reflective paper so as to prevent deforestation and climate change.

At home, Sunny said, “Ulla, why did you say I put curry in everything? I put spices in everything, not curry in everything. There’s no such thing as curry, in fact. It’s a fake word invented by the British.”

He distinctly heard his mother’s voice in his ear say, Who is this stupid person?

Ulla said, “Well, then all of India must have been conned by a British mistake. In every Indian restaurant I’ve been to, I see curry written all over the menu.” Later, when she thought Sunny had left for work, she telephoned her father: “He says he doesn’t put curry in everything, but he does. It drowns out all flavor in a burning inferno of pain.”

Sunny moved closer to listen, as gingerly as possible, but the floorboard made an equivalently slow toothache moan, and Ulla hastily hung up.

“I heard what you said.” Jig of brows. “Curry doesn’t equal chiles! You’re even getting what you have wrong wrong!”

“You were eavesdropping!”

“Maligning people is a worse crime.”

“It’s awful to be a snoop.”

Why was it that, in the Western world, snooping to uncover a crime was a worse crime than the actual crime? Ulla’s civilization was built upon wandering about naked and not snooping. Sunny’s civilization was based on donning your clothes and listening to every conversation.

How on earth had it come to pass that, in this Brooklyn idyll of triumphant multiracial calm, they’d reached such distrust? They reconciled this time at a bar on Lafayette, and from their reflection in the salvaged mirror behind the counter they saw they had reason to reconcile, for they were simply so beautiful together. As beautiful as or more beautiful than any of the other mixed-race couples in this neighborhood renowned for the beauty of its mixed-race inhabitants. The owner of the establishment had once asked if they were looking for work.

“Doing what?”

“Waitressing, bartending. I’m opening a restaurant on DeKalb called Urbane, and I want it to reflect how cool this neighborhood is.” Sometimes they fell to wondering if there was a joke being played, if the joke was on them. A joke like that of an Indian paying a lot of money to eat at a restaurant named Le Colonial.

“Should we leave for another neighborhood?” they sometimes asked each other. But then, seeing the new arrivals—Icelandic-Peruvian, Rwandan-Vietnamese, Dutch-Japanese, Cuban-Kazakh-Irish—beginning to produce children, the likes of which had never before been seen on Spaceship Earth, Sunny and Ulla couldn’t bear to leave this compelling scene that they themselves had helped to create, all these couples, two by two, who had begun to shove out the poorer residents, most of them Black. In a few years, nobody would remember this. But now, when they hurried home, Sunny and Ulla couldn’t avoid the anger that gathered in the shadows. They were wary of being mugged by residents of the projects just beyond.

Once, Sunny had been mugged as he walked home from his night shift at five in the morning, by a boy who appeared to have a gun, but it might have been a stick held under his shirt. When he woke Ulla, she insisted that a reluctant Sunny report the incident. The cops arrived and drove Sunny around in their patrol car to see if he could spot the boy again. But when Sunny saw the boy he looked away.

“No?” the detective asked, lean, alert, chewing nicotine gum.

“No.”

“Why did you do that?” Ulla was upset when Sunny told her. “They get away with a small thing, then another small thing, then they do a big thing.” But she knew that, if Sunny had identified the boy, she’d have taken the opposite side of the argument.

“We are more guilty,” Sunny said, “in the scheme of things.”

“Get out of our neighborhood, you bourgeois white motherfucker!” a man had shouted at a new neighbor moving in next door. And, although Sunny’s sympathy lay with the man who yelled, he knew it was a hypocritical sympathy. He hoped, in fact, to get a free pass, that as a dark-skinned person he’d be seen to have more legitimacy here than a white person. But his smiling at Black people on the street felt false and condescending, rooted in a wish to be accepted into this neighborhood of elegant brownstones and a quick subway line to Manhattan, while also cohabiting with Ulla, who was essential to his self-respect. He wondered if Ulla felt less guilty to be invading the place because she was with him. Both of them, in conversation with others like themselves, made certain to mention the well-off African Americans buying homes, to shift the conversation from race to class.

Sunny registered his own hypocrisy, too, when he looked away from other Indians he saw on the street—Indians who were also avidly ignoring him, trying to make it in America by avoiding one another, as if it were better to be one Indian than two Indians, better to be two Indians than three Indians. And better an Indian in New York than an Indian in India. Even more so an Indian in a village in France that was entirely empty of other Indians, especially Indians of the same class who would undo your poise, shine a light upon your shame, your lies.

And then there was Satya. Satya was Sunny’s childhood friend who would never in a million years comprehend that it might be better to be one Indian instead of two Indians or two Indians instead of twenty Indians. They’d attended Tiny Tots in Delhi together, in miniature blue shorts and miniature ties already knotted onto elastic bands that fit under their collars. They’d gone to Mount St. Mary’s in Delhi together, they’d had mumps together, they’d taken a delightful trip together when Sunny was a bachelor’s student following a story in Mysore about the government’s curtailment of subsidies for traditional weavers. In a case of misjudged importance, Sunny had been assigned to a scheme encouraging journalists to promote tourism and invited to stay at the Lalitha Mahal Palace Hotel. They had gone swimming in the maharaja’s pool at sunset, a warm wind carrying the aroma of the sere hills and stirring the papery bougainvillea. Satya—black hairs on his chest so extravagant they whorled and formed black roses upon him—couldn’t swim, but he pawed with such wild energy that his splashing carried him from one end of the pool to the other.

When they had dined in a romantic alcove of enamel-and-gold mirror-work, it had seemed a little peculiar, Sunny registered, to have Satya opposite him sharing a mango kheer and later to have Satya snoring by his side in bed, the pillows lavished with sandalwood perfume and rose petals. Their friendship had begun to take on the attributes that should have been assigned to a romantic partner, and perhaps they had each begun to wonder if their formative moments would take place not with wives or children but with each other. Together they had decided to apply to study in the United States, Satya for medicine, Sunny for a master’s degree in journalism. But here their paths had diverged—Sunny’s to New York City, Satya’s to Rochester. They missed each other, and one weekend, when Sunny and Ulla were still residing in the international students’ hostel, Satya had taken a Greyhound bus all the way down.

Ulla had claimed a deadline for a class, and Sunny was embarrassed by his girlfriend’s departure, as if she did not love him. Then, trying to look at Satya through Ulla’s gaze, he thought Ulla was disdainful of Satya’s roly-polyness, encased tightly within a home-knitted pullover, and his ardent and frank conversation. Keenly aware of Satya’s lack of sophistication, Sunny felt exposed by it—as though he’d tricked Ulla.

Satya didn’t mention Ulla as they walked about Union Square and Washington Square Park, and neither did he show the slightest tourist interest in Manhattan on this his very first visit. He noticed neither the skyscrapers nor the homeless people on the subway grates, neither the Buddhist monk on a skateboard nor a gaggle of models with poodles in booties. Interspersed with some aimless humming, he told Sunny about his running battle over the television in the residents’ lounge, where only Satya wished to watch “Golden Girls.” And why was it against the rules to dry his underwear out of the window?

Back in Sunny’s hostel room, Satya made a phone call: “Double the dose of amlodipine, test for uric acid and glucose, check the potassium level, prescribe gabapentin for the nerve pain.” He was being asked to give his opinion on a patient for whom he had been part of the monitoring team. How the different parts of Satya melded was a mystery.

He began to tuck sheets about the inflatable mattress on the floor, and got plumply into bed, folding both hands under his cheek as in a child’s picture of godly sleeping people. Sunny climbed into his bed as well and burst out, “So, what did you think?” For Satya not to have an opinion on the first occasion either of them had met a proper girlfriend was impossible.

“About what?”

“Ulla, of course.”

Deep soul sigh. “Ulla sees you as an Indian, and you see her as an American. The whole thing is based on a misunderstanding.”

“She isn’t only an American to me.”

“How can she not be an American to you?”

“I said only.”

“The main reason you want her is that she is American. You will get very angry at me for saying so, but, when you fight, you won’t be able to tell the real fight behind the fight.”

“A person is not only their nationality and race, Satya,” Sunny persisted. “After a bit, you no longer notice you’re a different color. At least inside the house you don’t notice it anymore.”

This had been a revelation to Sunny and Ulla, this mystical lightness.

When Ulla had heard Sunny with Satya, she’d said, “How chatty Indian men are!”

“Quarrelsome Bong!” she’d said of a Bengali she’d met at the gym.

“Tambram snob!” she’d said of a colleague. She’d pointed to a woman skipping the line “in her Indian manner.”

“I can say ‘Bong’ and ‘Indian manner,’ ” Sunny had said, “but you cannot.” But where could she have learned to brandish local prejudice with insider’s pride but from Sunny himself, or from Mala, her old nemesis?

“You criticize America all the time!” she’d retorted.

“God, you Protestants, don’t you ever talk openly?” he had said. And then, when he didn’t receive an answer, “Why don’t Americans have passports? Weren’t your parents curious about the world?”

“They had other priorities—like saving for my college fund. They weren’t rich.”

“With a big house and two big cars?”

“Two cars are a necessity where we live. And, in fact, my parents did go to Mexico.”

Ulla’s parents had exulted in Cancún because of the exchange rate; Sunny remembered a previous conversation about how they’d been excited to eat four tacos for a dollar twenty-five.

“Why do Americans endlessly talk about the best deal?”

“All travellers talk about the best deal.”

“No, the British still exchange the weather: Today a spot of sun, such fun; tomorrow rain, such a shame.”

“And what do Indians say?”

“Indians come up close and stare: ‘What, you are bald and still not married?’ ”

They’d laughed then.

“My hot samosa,” she’d called him.

“Ulla, you are not to say that!”

Almost choking with laughter: “O.K., O.K., my bad-tempered Bengal tiger.”

There was no hope all over again.

“Flaky blonde!”

“Bossy Indian patriarch!”

They were failing to keep their arguments personal, or unique and respectful to their individual beings, or even to the situation. Was it true, then, that there had been something to Satya’s warning? Should you live with an American in order to beat the American over the head for being one? Should you find an Indian to complain about Indians?

In the apartment below, through a gap near his shower pipe where there were some missing tiles, Lou Orsini could hear them fighting in their bathroom. If he were ever regretful that he was divorced, by the time he’d flossed his teeth he was inspired to compose a new song for the band he played in called the Love Handles: Thank the Lord I am divorced / You could not drag me back by force!

And, returning home one spring evening from the Korean deli, Ulla and Sunny unlocked their brownstone’s front door to find the letter from Babita propped on the stairs by the great carved mirror, oriental in its decorative details and its crown of colored glass glimmering in the dark of the entryway.

Babita Bhatia had left the house with her bulbul nose pointed sharply to the right, as Uncle Ravi, exiting his door, turned his squat nose to the left. She turned her bulbul nose sharply to the left as Uncle Rana, looking from his window, turned his philandering nose to the right. After collecting her mail at the gate and bringing it into her living room, Babita picked up her silver-inlay letter opener and sliced open the envelope sent by her father, the Colonel. She read the missive and studied the photograph of Sonia, then snorted and considered throwing the letter away. She spoke aloud to the ghost of her husband: “Ratty, when Sunny marries, I will be more alone than I am now. You didn’t take care of me! Is this a country where women can manage on their own?”

She got up and surveyed herself in her three-panelled dressing-table mirror. Did her sari’s pink run too garish for someone her age? She was forty-nine years old, her skin was still as plush as a magnolia petal, her profile still pert.

Angry at feeling old when she was yet young, and wanting to defuse a threat by ridiculing it, Babita sat down at her desk and composed a forwarding note to enclose with the marriage proposal for Sunny. As she wrote, though, her malaise worsened. How desolate it was to have to hoard one’s thoughts and jokes for future company, how tedious to translate them into a letter.

She put down her pen, walked out on her bedroom terrace to look across the street at a building site. In the early years when Delhi’s one-story bungalows were being built up into flats, the taller residences had been divided into three flats, but now they were a level higher and being divided into eight.

Babita watched the laborers’ children playing astride a tunnel drainpipe, made steady by a heap of sand, as their parents worked. Swaying from side to side, they sang a song in a language Babita could not identify. Where did they come from? Their hair was reddish and rough, their bellies swollen with malnourishment. She found she was surprised, then dismayed by her own assumption that poor, malnourished children did not have songs to sing. When they saw her looking, ten mischievous faces sparkled at her; they were too young to know their lives offended.

She went inside, applied deodorant to her underarms, and called, “Vini-Puni, gym shoes!” Then, hitching her sari higher, she laced the gym shoes, leashed her dog, Pasha, and prepared to set off on her evening constitutional, picking up the letter she’d just sealed. She paused. Why needlessly upset Sunny with a girl who would not interest him?

But to reiterate her good character to herself—she had been asked to forward it, after all—she gave the envelope to Vini-Puni to post.

“And don’t go making eyes at the drivers,” she warned.

Vinita glowered because the drivers were making eyes at her, not she at them.

In Lodhi Gardens, Babita walked briskly and competitively, accelerating to overtake others, shouting “Right” to alert people that she was approaching them to their right, or “Left” if she planned to triumph to their left. They inevitably became confused, for they had never heard of this protocol, and scattered like brainless fowl as she sped about the paths that circled the turbaned tombs dating from the fifteenth century. When Pasha tried with all his might to pull her toward the pond filled with barely treated sewage water, people stopped and chuckled at the sight of a rich woman being humiliated by her expensive dog. As she dragged unwilling Pasha along—she knew if he managed to get into the pond, he’d sit obstinately in the opaque sludge crawling with mosquito larvae until nightfall—she caught a gentleman pissing into a rosebush and pounced. “For shame! Because of people like you our nation won’t improve.”

He hurriedly zipped up, but, this evening, the usually life-affirming activity of overtaking other walkers and having altercations with men pissing in public depressed her. Perhaps it was the weather that disheartened: muggy, spore-ridden, and netherish. Perhaps it was the tossed picnic plates that lay on the scummy pond surface without sinking, or the irritating fact that from the bushes the legs of lovers protruded, their upper bodies entwined and shrouded by foliage, the better to hide their kisses. She felt like chasing them out, too, just as she had the pissing man. Perhaps she was wearied by the long drive to the park in office traffic—whatever health benefits she’d accrue by a loop about Lodhi Gardens would be undone by breathing in petrol fumes.

Once she was home, Babita showered. The water spurted momentarily hot from the roof-tank pipes that had been heated by the sun all day, but eventually they disgorged cooler depths. She powdered herself with Pond’s Dreamflower talc, and when she sat down to dinner she maintained the protocol she’d set, alternately praising and criticizing to instruct yet encourage the staff: “The fish is fried crispy, but the pudding is too tight.”

The girls would never be excellent cooks, no matter how meticulously she trained them—what it took was a thoughtless measure of spice, a certain nonchalance about the kitchen.

Vinita ignored her.

Babita felt her temper rise. “Didn’t you hear what I said?”

“Haa.”

“What ‘haa’?”

“Ji haa.”

“And what did I say? Repeat what you heard so I know you’ve understood me correctly.”

“Ji haa, Auntyji, the pudding should be less tight,” Vinita said. Babita sensed a mocking tone.

“Don’t put that hair oil in your hair, you are overwhelming the house like an attar shop near Jama Masjid.”

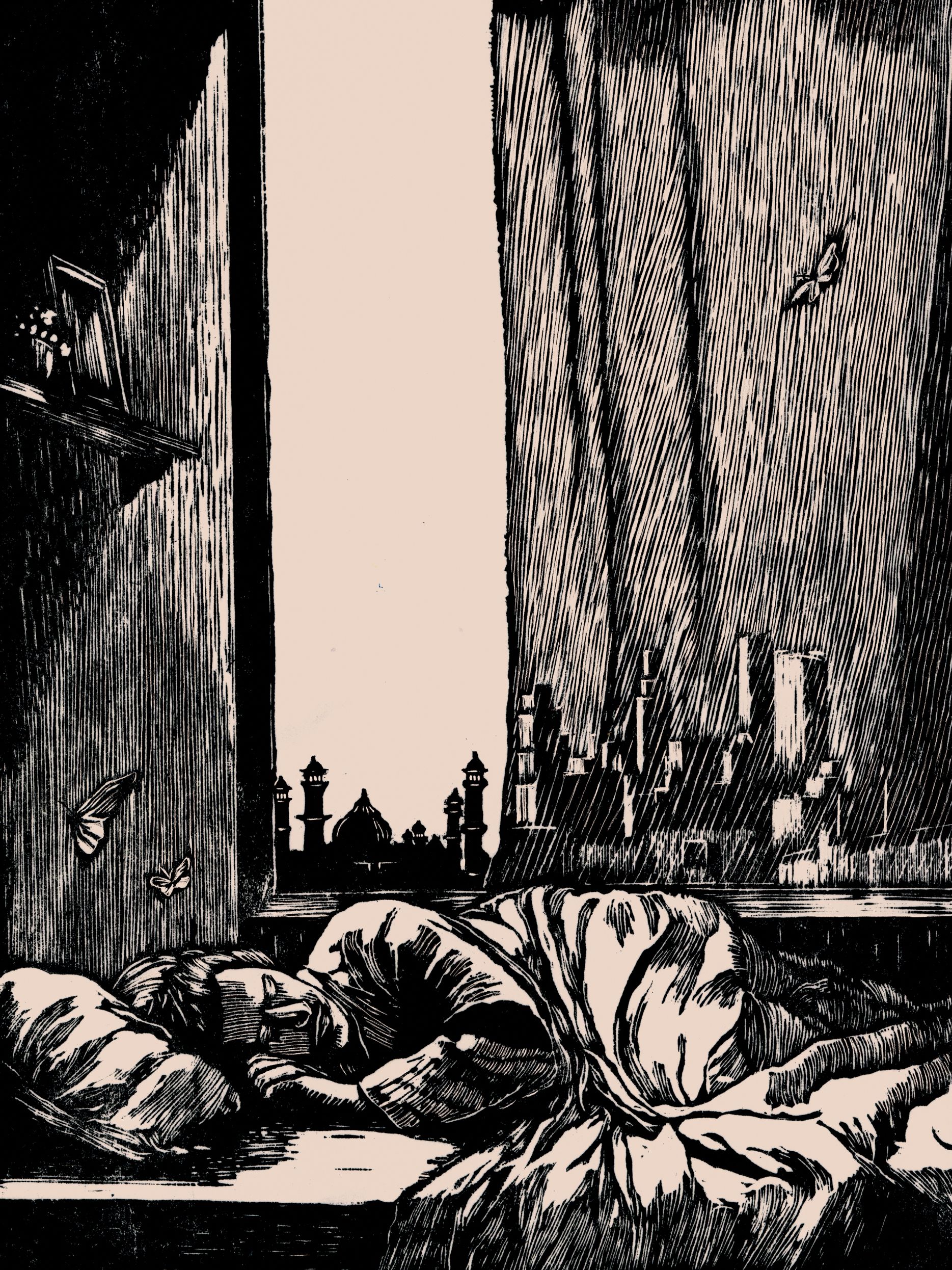

At night, Babita tossed so much that her nightgown wound around her and she suffered indigestion. She listened to the watchman bringing down his wooden staff and blowing his whistle on his rounds. She thought this kept only the watchman safe—thieves learned that they might rob on the other side of the neighborhood from where he was. On the other hand, if he hadn’t been instructed to march and whistle, he’d feel free to nod off. She switched on her lamp. For a span of time, after her husband’s death, which had occurred when she was thirty-three years old, she and Sunny had shared a bed. One day, Sunny had returned to his own room without a word. This had upset her profoundly, but she’d had no way to articulate her upset. Her response was irrational. They hadn’t spoken for a week, and neither of them had ever made mention of this episode. Years later, Sunny had burst out with “I am not your spouse. You have to let me be. It isn’t fair!”

It had been necessary to send him to New York to make his own life.

Babita sought her water glass. She confronted the fact that it was not Vini-Puni’s insolence or the too-tight pudding. It was not the people at the building site with their close-up poverty. Not her precarious position as a widow in a household united against her. Not the ammoniacal fumes of men pissing in the park. Nor the legs of kissing couples protruding from the bushes.

What curdled was the photograph she had enclosed in the letter to Sunny. It was Sonia’s face planed like a panther: thick eyebrows and blazing eyes, sad and defiant, angry and accusing, a magnificent mouth of down-turned reproach.

Two weeks later, early in the morning, when in Delhi and across the nation widows and widowers made their phone calls to reassure themselves they were not alone although night had informed them otherwise, Babita telephoned Sunny from the phone on her bedside table. “Sunny,” she said. “Sunny, did you receive that very silly letter?”

The crows outside her window raised their wings of doom and cawed. Soon the sun would wrest control, everything set by then in stone.

Sunny heard his mother’s voice enmeshed in a thicket of kava kava kaw that transported him to his home city and made him remember that each waking moment of a crow’s life is aggressive: their voices warned, their wings sliced like swords, they robbed and killed all day.

“I should let you work,” Babita began. “Work comes first.” She feigned indifference, but her armpits itched. “Do you remember that family in Allahabad?”

“No, and less do I care,” Sunny said. “Don’t meddle, Ma. You think it’s harmless, but it is harmful.”

Leap of heart. “Who is meddling?” she exclaimed. “You’ll find someone on your own when you are ready.” She hurried this sentence to prove it wasn’t that she didn’t want Sunny to find someone, just not this person now.

“Well, I did find someone!” It came bursting out, stimulated by Ulla’s bitterness.

“What do you mean?”

“I have a girlfriend!” he shouted, as if he’d been afflicted with one.

“Who?”

“It doesn’t matter who! Anyway, it’s not going to last.”

“It isn’t?”

“No! Not with all the nonsense you’ve been dragging into my life.”

Babita immediately telephoned the Colonel, raising her voice above the crows at both ends of the line now. She reported, “Sunny is not interested. He will need somebody more modern.” Dismissing Sonia, she considered the staggering news of an American girlfriend.

Vinita came in with the tea tray and the newspaper. Babita turned to the travel page first and found an account of an Alaskan cruise. It had become something of a fad for Indian children who’d achieved an American life to treat their parents to an Alaskan cruise, to allow them to experience for a week what they’d bequeathed their children for a lifetime—the bliss of being able to pretend they were not Indians and that India didn’t exist. They might see enough white people and empty white landscapes there to convince them that this was so. What was so odd, Babita reflected, was that this striving to escape India felt patriotic: if you were a worthy Indian, you became an American. ♦

This is drawn from “The Loneliness of Sonia and Sunny.”