When the late Pope Francis was elected, a dozen years ago, and famously declined the pomp and perquisites typically associated with the office, among his renunciations was the use of the papal summer residence—a seventeenth-century palazzo in Castel Gandolfo, about fifteen miles south of Rome. Generations of Popes had enjoyed the use of the mansion, which overlooks a volcanic lake and is surrounded by spectacular terraced gardens. The palazzo is now a museum where visitors can admire a gallery of papal portraits, of varying quality, and imagine the dreams that visited the successive occupants of the papal bedroom, with its narrow twin bed. Castel Gandolfo is also home to one of the Holy See’s more unexpected institutions: the Vatican Observatory, which since its founding, in 1891, has been dedicated to the scientific study of the heavens.

Guy Consolmagno, the director of the observatory, first came to Castel Gandolfo as a newly minted Jesuit brother, in 1993. When I met him outside the palazzo, early this spring, he gestured at a window overlooking the building’s courtyard. This was the location of his first, decidedly modest bedroom in the mansion. Consolmagno, who grew up in suburban Detroit and retains a buoyant, emphatic, Midwestern manner, told me, “The Pope then was John Paul II, and when he was first elected he had made a rookie mistake, as we say in America. Somebody, a journalist—one of those terrible journalists—had asked him, ‘What’s your favorite hymn?’ And, being a fool, he actually gave the name of a hymn that he happened to like. So, every Sunday during the summertime, when he was living here, the doors would open at 10 a.m., and this place would be filled with two thousand Polish pilgrims singing that hymn underneath my window. I got totally sick of it.” Consolmagno never got sick, though, of being saluted by the Swiss Guards stationed at the palace gates.

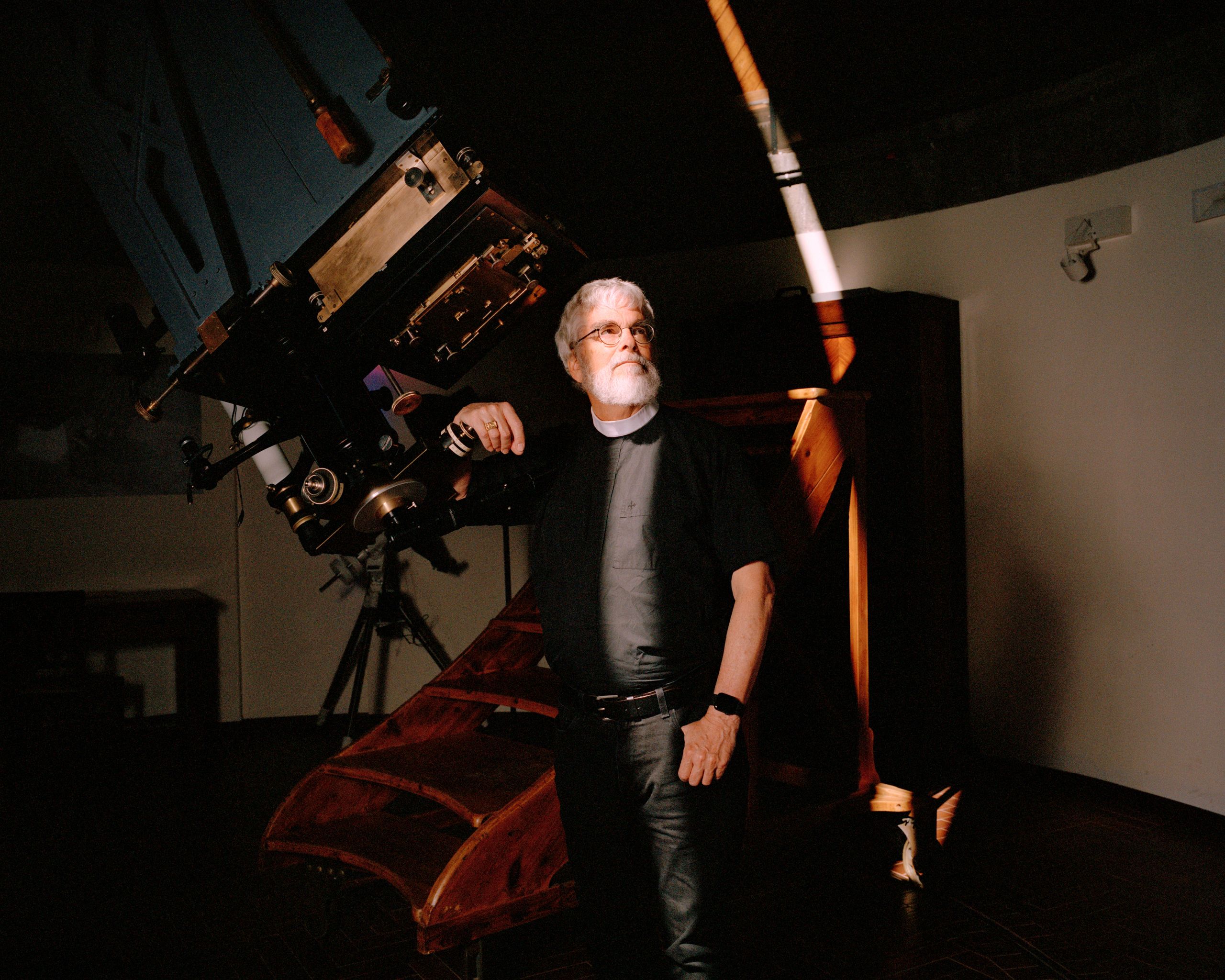

Consolmagno, who has a prodigious white beard, wavy gray bangs, and dark, beetling eyebrows, is one of fifteen scientists who currently make up the scholarly staff of the Vatican Observatory—all Jesuits and, inevitably, all men. (Their meals, perhaps equally inevitably, are prepared by a local woman.) At any given moment, about half of the fraternity is in Castel Gandolfo, which has been the institution’s home since the nineteen-thirties—although, for the past fifteen-odd years, the staff’s living quarters have been situated in a former convent a short distance from the palace. The other half of the team is in Arizona, a state that offers a remote mountain environment more conducive to astronomical observation than the light-polluted suburbs of Rome do. In the early nineties, at the Mt. Graham International Observatory, near Tucson, the Vatican installed a powerful four-million-dollar telescope and an astrophysics facility, together known as the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope, or VATT. Consolmagno, like many of his colleagues, shuttles frequently between Italy and Arizona, rarely spending more than a few months in one place.

Consolmagno likes to say that, when he arrived in Castel Gandolfo, the director at the time, Father George V. Coyne, told him that he had only one job: to do good science. At first, Consolmagno was engaged mostly with taking painstaking measurements of specimens from one of the world’s preëminent collections of meteorites, which was bequeathed to the institution, in the early twentieth century, by a French nobleman, the Marquis de Mauroy. Consolmagno and several colleagues developed a new method for measuring the density and porosity of meteorites. The approach is not a million miles from the revelation delivered to Archimedes as he displaced water in his bath: the specimens are submerged in a vessel filled with helium gas, the molecules of which are small enough to penetrate tiny nooks and crannies in the rocks; if the specimens are then submerged in a vessel filled with glass beads that are tiny but too large to penetrate such spaces, the difference between the two volumes helps reveal the rock’s porosity. Sara Russell, a planetary scientist at the Natural History Museum in London—and a friend of Consolmagno’s since the mid-nineties, when they met on a meteorite-hunting expedition in Antarctica—told me, “He started out making simple measurements, and over the years his method got more and more sophisticated, and managed to make fundamentally important observations.” Among other contributions, the Vatican Observatory has made available to scientific researchers fragments of a rare meteorite, known as Chassigny, whose chemical composition suggests that it originated in the mantle of Mars.

Like research institutions that are not staffed with those who have taken religious vows, the Vatican Observatory collaborates with scientific colleagues around the globe. These have included, in recent years, NASA, whose OSIRIS-REx mission (2016-23) collected samples from the Bennu asteroid, which measures a third of a mile across and has been calculated to have a not infinitesimal chance of colliding with Earth in the twenty-second century. Bob Macke, another Jesuit brother in Castel Gandolfo, has developed a specialty in documenting the properties of meteorites, and several years ago he was invited to join an international team analyzing the Bennu samples; in 2023, he built a device specifically adapted for carrying out these delicate measurements. “NASA needed help with a mission. The Vatican came to the rescue,” read one headline about the collaboration.

Although the Vatican Observatory produces a wealth of peer-reviewed science, its structure is much different than, say, an astronomy department at a university. The Arizona telescope’s daily operations are funded by private donors to a not-for-profit foundation, and the Jesuit staff’s administrative costs and salaries are covered by the Holy See. Scientists at the observatory are liberated from the secular scholar’s pursuit of tenure, grant money, and commercial investment; moreover, the Jesuits, having taken a vow of poverty, have extremely low living costs. Like the builders of a fourteenth-century cathedral, they are able to take the long view. In Castel Gandolfo, Consolmagno explained that, nearly two thousand years ago, the site had been the location of a palace belonging to the Emperor Domitian. (Some fragmentary ruins remain on the castle grounds.) Christians were exiled under his rule, “and now his gardens belong to the Pope,” Consolmagno said as we walked beneath cypresses and umbrella pines, with evident satisfaction at the comeuppance.

As director, a post he has held for the past decade, Consolmagno spends far less time peering through a telescope or a microscope than he once did, and far more time explaining to the public why doing those things is not incompatible with religious conviction. He is constantly on the road, all over the world, giving talks to religious and secular audiences alike, often billed as “the Pope’s Astronomer.” At these events, he fields such questions as whether there is any recorded evidence for an actual Star of Bethlehem. (There is nothing conclusive, but scientists have identified various suggestive celestial phenomena in the years around the birth of Christ, including alignments of planets which might, to the naked eye, look like bright stars.) Consolmagno is also well known in the science-fiction community, of which he became a devout member as a young adult. He still shows up at sci-fi conventions whenever he can. His preferred subgenre is the space opera, with its dramatic adventures and heroic plots; he confesses to reading such works on his phone before bed, in violation of sleep-hygiene strictures. Patrick Nielsen Hayden, an editor at Tor Books, which publishes science fiction, and a friend of Consolmagno’s from the scene, told me, “He’s, like, the least proselytizing dude you could possibly imagine, given that he’s a Jesuit brother and it permeates his whole identity.” Nielsen Hayden, who characterizes himself as a “grumpy, reluctant, argumentative Catholic,” added that Consolmagno “has a tremendous capacity for affable friendship and civilized exchange with people from belief structures completely different from his own.” Consolmagno has written numerous popular-science books for general audiences, ranging from a plainspoken credo, “Finding God in the Universe,” to the puckishly titled “Would You Baptize an Extraterrestrial? . . . and Other Questions from the Astronomers’ In-Box at the Vatican Observatory,” which he wrote with Father Paul Mueller. (The short answer to the extraterrestrial question: only if the alien asked him to.)

Brother Guy, as he is widely known, never suggests that science might offer a means to prove the existence of God, or even to indicate a high probability of His existence. Consolmagno does not subscribe to what is known as the anthropic principle, which argues that the physical properties of the universe are so fine-tuned within the extraordinarily narrow range allowing for the emergence of intelligent life that the cosmos must have been made for us. Nor is he tempted by concordism—the idea that the discoveries of modern science can prove that events described in the Bible are grounded in reality. “Scripture was not written to tell you about the natural world,” Consolmagno told me. “It was to tell you about God.” The most egregious example of concordism, he said, was offered by Pope Pius XII, who had studied science and was interested in astronomy; in 1951, Pius XII gave a speech to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in which he characterized the big bang as confirming the Book of Genesis by “bearing witness to the august instant of the Fiat Lux, when, along with matter, there burst forth from nothing a sea of light and radiation.” Pius XII stopped suggesting that the big bang required the orchestration of God after he had a conference with Georges Lemaître, the Belgian scientist and Catholic priest who had laid the groundwork for the theory with his hypothesis that the universe had expanded from a “primeval atom.”

Pope Francis, under whose papal reign Consolmagno was appointed head of the Vatican Observatory, was a Jesuit, the first member of that order ever elected to the papacy. Although Francis did not have a particular interest in astronomy, he believed that scientific inquiry and the mission of the Church could meaningfully intersect: among his most significant statements was the encyclical “Laudato Si’,” which urged action against global warming and environmental degradation. Consolmagno approved of this intervention, and also admired Francis’s humility and spirit of intellectual openness. Unlike Lemaître, Consolmagno and his colleagues do not advise the Vatican on celestial matters; they are left to get on with their work, and have nothing to do with doctrine. Consolmagno rarely goes to the Vatican proper; he’s too busy elsewhere. When I visited him in Castel Gandolfo, he told me it had probably been a decade since he had been inside St. Peter’s Basilica.

Consolmagno believes in the big bang, at least as a provisional explanation of the universe’s origins, and also in a creator God who exists before and beyond the big bang. In his understanding, the spheres of science and religion do not entirely overlap. Rather, they “live together—the one doesn’t replace the other,” he told me. “Using science to prove religion would make science greater than religion. It would make your version of God subservient to your understanding of the universe. And not only does that make for a pretty weak God, but it is also crazy, because in a thousand years’ time the scientific questions that people ask are going to be very different. Science goes obsolete—it doesn’t progress otherwise.”

Among the research projects to which the telescope in Arizona has contributed is a fifteen-year analysis of objects in the Kuiper Belt, a band of ice-rich asteroids in the distant solar system. Many of the objects have been found to have curious orbits that, according to some scientists, suggest they are under the gravitational sway of a massive planet—as yet undiscovered—beyond Pluto. Other colleagues have used the VATT to observe near-Earth asteroids that may offer the possibility of commercial exploitation. Consolmagno characterizes the Vatican Observatory as deliberately doing middle-of-the-road science and practicing middle-of-the-road religion. “If people think you have to be a weird kind of scientist to be religious, or a weird kind of religious to be a scientist, then we’ve missed the point,” he said. “The point is that our faith—our ordinary faith—fits perfectly with our ordinary, but wonderful, delightful science.” Some years ago, the International Astronomical Union named an asteroid in honor of his contributions to science. Somewhere between Mars and Jupiter, the asteroid 4597 Consolmagno continues its celestial course.

The Church’s study of the stars dates back at least as far as the late sixteenth century. Under the leadership of Pope Gregory XIII, a meridian line was installed in the Vatican to illustrate the need to reform the Julian calendar. A Jesuit, Christopher Clavius, helped propose that the Vatican adopt the Gregorian calendar, which it did in 1582. According to the historian Jonathan Wright’s book “The Jesuits,” when the realignment caused ten days to be subtracted from the year, mobs across Europe attacked Jesuit houses to protest the time stolen from them.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, an observatory was built atop the Vatican Library and Museum, in what is known as the Tower of the Winds. Eclipses were observed and meteorological measurements were taken. The Vatican Observatory that exists today was set in motion by Pope Leo XIII when, in the late nineteenth century, he devoted a second observation tower in the Vatican to astronomical work. Fortuitously, this occurred around the time that an international community of astronomers, at a gathering in Paris, decided to embark on a collaborative project to make the first photographic map of the sky. Responsibility for charting different zones of the heavens was assigned to different national observatories; the Vatican was granted its own share of the sky to map, and was thus able not only to participate in cutting-edge science but also to assert its identity as a sovereign nation, despite being less than a fifth of a square mile. By the thirties, however, light pollution had made the center of Rome inhospitable to the observatory, and the Pope—now Pius XI—offered the use of Castel Gandolfo as a future base of operations. Two new telescopes were built there, and the running of the observatory was formally taken over by the Society of Jesus, better known as the Jesuits, the Church’s most intellectually powerful division.

During the Second World War, the papal property in Castel Gandolfo was neutral territory; two thousand people displaced from local villages flooded into the palazzo’s gates to seek shelter, sleeping in a grand hall previously used for papal audiences or dwelling in a shantytown on the castle grounds. In subsequent years, research once again flourished, with the construction of another new telescope in the papal gardens. It was through this device that the Pope—now Pope Paul VI—peered at the moon on the night of July 20, 1969, when Apollo 11 made its historic landing. Afterward, he addressed the astronauts: “Honor, greetings, and blessings to you, conquerors of the Moon, pale lamp of our night and our dreams! Bring to her, with your living presence, the voice of the spirit, a hymn to God, our Creator and our Father.”

At the time of the moon landing, Consolmagno was about to begin his final year of high school, in Detroit. His father, an executive at Chrysler, had soldered a recording device to the family television to preserve the audio of the momentous occasion. Later, in college, Consolmagno taped over most of the recording with music, but, he recalled, “the very tail end was the actual landing, so, whenever I got to the end of whatever that record was, I would hear, ‘Drifting to the right a little. . . . Tranquility Base here, the Eagle has landed.’ ” His family was Catholic on both sides; his mother, a schoolteacher, was of Irish descent, and his father, who had been a journalist before becoming a P.R. man for the auto industry, traced his roots to a village in southern Italy. (Family legend has it that Consolmagno’s great-grandfather immigrated to America after being run out of town for uprooting and then stealing other people’s fig trees.) As a boy, Consolmagno was taught to identify the constellations by his father, but his academic interests grew to include the humanities. “The smart kids at the Jesuit high school did Latin and Greek, so that’s what I did,” he told me. He enrolled at Boston College to study history, but wasn’t happy there: “It was a party school, and I didn’t like to party—it made me uncomfortable.” He transferred to M.I.T., lured in part by the science-fiction club’s impressive library, and switched his major to Earth and Planetary Science.

After getting his doctorate, at the University of Arizona, in Tucson, he went back East for postdoctoral work at Harvard and at M.I.T. By the time he was thirty, however, Consolmagno had failed to gain traction in his academic career, and, perhaps not coincidentally, had become disillusioned with the prospect of pursuing ever more esoteric science. “I’d be wondering, Why am I doing this?” he said recently. “Why am I beating myself up writing papers about the moons of Jupiter when there’s people starving in the world? Papers that only five people in the world are going to read, and two of them are my enemies?” He enrolled in the Peace Corps and went to Kenya, hoping to be sent to teach at a rural school. His academic credentials, however, led him to be assigned to one of the country’s premier high schools, in Nairobi, and then reassigned to a university there, training others to become science teachers. On weekends, he would travel to visit friends who had been assigned to remote schoolhouses, where he gave talks about astronomy. During these visits, he often set up a telescope so that locals could gaze in wonder at the moon.

After nearly two years in Africa, Consolmagno got a job teaching at Lafayette College, a liberal-arts school in Pennsylvania. He loved the work, but still felt that something was missing in his life. As an undergraduate, he had flirted with the idea of joining the Jesuits, having admired the mental acuity of the members of the order he’d known in high school, but he had decided that wanting to be part of a clever cohort was not a sufficient motivation. Now he considered the possibility of becoming a Jesuit brother—a member of the society who takes vows and lives in a community with other Jesuits but is not ordained. “I loved teaching, and I thought, Well, this must be what I am good at, and I wouldn’t have to do the priest things that I wouldn’t be very good at, like hearing people’s confessions,” he told me.

For Consolmagno, abandoning secular life wasn’t the hard part. “I can’t relate to the things that most people are tempted to do,” he said. “Drinking? I’ve tried. It’s like drinking mouthwash. I dated for twenty years. I wasn’t happy.” He wasn’t tempted by gambling, and found that he had no hunger for worldly advancement. “It’s not to say I’m a saint,” he said. “It’s just that I can’t relate to people who do have real struggles with these things.” When Consolmagno told his parents of his intention, his mother, who was devout, was worried about the lifelong commitment. “And my dad’s answer was ‘I could have told you that in high school,’ ” Consolmagno told me. “He’s not the only one who told me that, including women I dated in high school.”

Jesuits undertake extensive studies in philosophy and theology, and they also take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Consolmagno jokes that life as a graduate student prepared him for the first two vows; the third was the most challenging. Yet, by the time he completed his training, at the age of thirty-eight, he was willing to go wherever the Church wanted him to be, and to do whatever it asked. To his surprise, he was sent to a hilltop castle outside Rome, and he was encouraged to do whatever he liked with its celestial rock collection.

The idea that religion and science are inevitably at odds is widespread among secular observers. The Church, in its two millennia of existence, has played a role in this perception, by punishing people who dared to challenge its orthodoxies. In 1600, the cosmologist Giordano Bruno, who proposed that the universe was infinite and that stars were distant suns, was burned at the stake for his heresies. Galileo Galilei, who, in 1632, published a book supporting the Copernican theory that the Earth revolves around the sun, was accused of heresy, obliged to recant, and condemned to house arrest. It was not until 1992 that the Pope at the time, John Paul II, officially acknowledged that the seventeenth-century clerics who had prosecuted Galileo were wrong. (As for Bruno, the Church has conceded only that the killing was a “sad episode.”)

The secular world, meanwhile, has often attacked the Church as a peddler of absurd fantasies. In recent decades, writers grouped under the rubric the New Atheists—among them Christopher Hitchens, the swingeing author of “God Is Not Great,” and Richard Dawkins, who wrote the intemperate book “The God Delusion”—have decried organized religions for their damaging superstitions and mystifications, and have championed an explanatory rationalism in their stead. In “God Is Not Great,” Hitchens, who died in 2011, wrote, “If you will devote a little time to studying the staggering photographs taken by the Hubble telescope, you will be scrutinizing things that are far more awesome and mysterious and beautiful—and more chaotic and overwhelming and forbidding—than any creation or ‘end of days’ story.” The New Atheists were revisiting debates from the nineteenth century, when influential critics, among them Andrew Dickson White, the first president of Cornell University, sought to reëxamine established religions in the light of recent scientific discoveries. In “A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom,” published in 1896, White wrote that “dogmatic theology”—rigid interpretations of religious doctrine—inherently clashed with scientific findings, which were constantly evolving because of new thinking and technologies.

According to Consolmagno, the arguments put forward by the New Atheists and their ilk invoke what you might call a straw God. “When I say, ‘I believe in God,’ it means that I believe in one God, which means there are a whole lot of versions of God out there that I don’t believe in,” he told me. “An atheist, in order to be an atheist, has to have a really clear idea of who the God is they don’t believe in. More often than not, they are right—the God they don’t believe in I don’t believe in, either.” Consolmagno’s Catholic faith does not require that he believe the world was literally created in seven days, and he pities would-be astrophysicists who grew up in fundamentalist Christian traditions. Once, while visiting Oral Roberts University, in Tulsa, he stumbled across a way of expressing his perspective on the Book of Genesis: “I pointed out that the seven days of creation tell us not about creation but about God,” he recalled. “If you put that emphasis on it, I think you get closer to what the author of Genesis really wanted to do, which was to talk about God. What’s the goal of Genesis? It’s the seventh day, the Sabbath. And what’s the Sabbath? It’s when we start thinking about the universe, and the creator, rather than just worrying about feeding ourselves, and that’s what makes us people, rather than animals. God calls us to be astronomers. Not only is it clever—it might even be true.”

For Consolmagno, human accounts of occasions when the divine has made its presence felt—including reports of miracles—constitute data that he would be foolish to dismiss out of hand. “I’d be a pretty poor scientist if I rejected the evidence of so many experiences (including my own) that prayers are answered and that miracles do occur, just because they don’t fit my preconceived theory for the predictability of the universe,” he observed in “God’s Mechanics” (2008), in which he interviewed various other religious scientists and explored the basis for his own faith. Consolmagno wrote, “God is God; he can, in theory, do anything he likes. But, by seeing what it is he actually does and how he does it, I can begin to get an idea of what it is he likes to do and how he likes to do it. And I would have to say that the God who created this universe is someone who loves to act with elegance, economy, predictability, and consistency.”

Although Consolmagno enjoys talking about his thoughts on science and religion, he has generally refrained from discussing his views on politics. But the American government’s recent assault on research universities, and its dismantling of international health services—in the realm of astronomical sciences alone, the annual funding for grants from the National Science Foundation has been slashed by more than half—has prompted him to be more outspoken. “The uncertainty has already created chaos in my field, and certainly in the health field,” Consolmagno said. “It will be a while before it recovers just from this chaos, and that damage has already happened, and people will die because of it.” He went on to explain that President Trump is “doing damage not only to the science that I love but to conservative principles that I might want to embrace. He’s a terrible representative of that. So it’s one thing to say, ‘I hate him because I’m a liberal,’ but I think it’s more important to say, ‘I despair of him in the places where I’m not a liberal.’ ”

Recently, the new Pope, Leo XIV, gave a speech to the College of Cardinals in which he said that the Church was eager to offer “the treasury of her social teaching” to address “developments in the field of artificial intelligence that pose new challenges for the defense of human dignity, justice and labor.” Consolmagno similarly feels that the Church could play a role in establishing ethical norms for space exploration, especially in an era in which billionaires are sending up their own rocket ships. At a recent lecture that I saw Consolmagno deliver in a crowded church hall in Glasgow, he suggested that the Vatican, as an independent country, could serve as a neutral place where questions of scientific ethics and priorities can be hashed out among nations. He cited a workshop that he and his colleagues held a few years ago to discuss the peaceful use of outer space. He noted, “The rules are only as good as what people will agree to follow. With some of the personalities involved, I fear that it’s going to take a disaster in space before they decide, ‘O.K., we need to get our act together.’ ” He went on, “We are human beings, and, ultimately, when we have people living on the moon, there are going to be drunkards. There are going to be guys who smell of stale beer, like the guys in my freshman dorm. But there are also going to be people who love what they are doing, and love the people they are with, because that is what it means to be a human being, and to be a sinner drawn to the God who loves us all.”

When Pope Francis died, in late April, Consolmagno was on tour in the United States. A few days after the funeral, Consolmagno was in Glasgow, to deliver his lecture. When we met in the city, he said of Francis, “He was a wonderful person who I had gotten to know, who had gotten to know me. When you would walk into a room, his face would light up in a smile—and, boy, what that did to you when he reacted like that. I’ll miss his good humor, and his gentle support.” We were sitting in a Tim Hortons, where Consolmagno had ordered an enormous cup of watery coffee and an execrable-looking apple pastry—despite living in the land that graced the world with the cappuccino, he is sometimes homesick for the comestibles of the Great Lakes.

Consolmagno told me that he had no preferred candidate for Francis’s successor. “The most important thing is that they are people of God, that they are really committed to the religion, that they have faith in the Holy Spirit,” he said. Lots of cardinals have little understanding of science, “and they’d be the first to admit that,” he added. “In some ways, they’re easier to work with. It’s the ones who think they know that you kind of get worried about.”

There were scattered clouds in the sky over Rome on the night of May 7th, when the cardinals were in seclusion in the Vatican, having not yet selected a new Pope from among their number. Consolmagno was still out of the country—he had more talks to give in Scotland—but I happened to be in Rome. There, on the elegant Ponte Sisto, a stone footbridge commissioned, in the fifteenth century, by Pope Sixtus IV, an enthusiastic young man had set up a telescope, and was charging passersby a few euros each to look at the moon, which was waxing gibbous. I asked him if he knew about the Vatican Observatory. “Of course!” the man said. “They’re the best.” I took a turn at the eyepiece and gasped: I could see the moon’s silvery surface, so dense with craters that it appeared almost crenellated in its texture. Like the Kenyans who looked through Consolmagno’s telescope decades ago, I was filled with wonder.

Consolmagno, in his writings and in conversation, is reserved about giving testimonials of his personal experience of God. Perhaps the subject is too private, or the moments of conviction too fleeting. When we first met, in Castel Gandolfo, Consolmagno spoke of the awesome and sometimes destructive powers present in the physical universe, from tsunamis to earthquakes to supernovas. “Things that can cause pain are also things that have an innate beauty in them, and bending your brain around that is one of the great challenges of life,” he remarked. “Just like the pain of trying to understand physics—why does it have to be so hard? And yet there is a sublime beauty to how the universe works that we can only begin to touch. That, to me, is where I see the presence of God.” Does he see the presence of God when he looks through the Vatican’s telescopes? Yes, he said, but that’s only part of what he sees: “I see the presence of God—and I see the astronomy instructor who is explaining that thing to me, and I see my father telling me as a child, ‘That’s Jupiter,’ and I see the joy I felt as a three-year-old looking at the stars, or the joy as a ten-year-old watching the moon set, and seeing that it actually moves. All of those things, layered together.”

Looking at the moon suspended in the sky over the Tiber, I remembered what Consolmagno had told his audience in Glasgow: that he doubted his faith “only about two or three times a minute.” The line got a big laugh. “But the opposite of faith isn’t doubt,” he continued. “The opposite of faith is certainty. Being comfortable with doubt, just as I doubt my science, just as I am constantly questioning my science, I do that because it makes my science stronger, and I do that because it makes my faith stronger.” Consolmagno went on to describe a sense of transcendence he had once experienced while laboring over his meteorite measurements in his laboratory in Castel Gandolfo. “You take a lot of data, and you plot everything against everything else, to see if there’s a pattern,” he said. “And there was one moment where—oh, my God—the pattern was perfect. The density matched with the magnetic susceptibility on a perfect line, with one type all over here, and the second type over there. I had this feeling of God peering over my shoulder, going, ‘Isn’t that cool? Let me show you the next one.’ ” Nonbelievers might share this occasional sense of numinous exhilaration, even if their interpretations of the data diverge, Consolmagno acknowledged. He said, “Even scientists who don’t believe in God have to believe in ‘Oh, my God.’ ”

When the cardinals elected Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost to be the Pope, after slightly more than one rotation of the Earth, one of his first public acts was to make known his adoption of a new papal name: Leo XIV. The choice was inspired by Leo XIII, the late-nineteenth-century cleric who was outspoken in his support for working people and the poor—and who also happened to be the founder of the modern Vatican Observatory. In an e-mail the day after the conclave reached its decision, Consolmagno told me that he had never met the new Pope, but that everything he had heard about him was very encouraging. “It’s great fun to think of somebody who grew up in the Midwest not far from where I grew up, and as I understand it he even went to high school in Michigan,” Consolmagno wrote. “I think that means it will be very easy to talk with him, because there won’t be the barrier of language or culture; I think we will be able to understand each other.” After ten years as the Pope’s astronomer, Consolmagno would like to retire soon—the travel is getting to be a bit much—but his vow of obedience means he’ll stay at his post as long as he’s needed. He wrote, “As for my future plans, it’s entirely in his hands.” ♦